The Flathead Beacon is a weekly print newspaper and daily online news source serving Western Montana’s greater Flathead Valley. Headquartered in Kalispell, Montana.

www.flatheadbeacon.com

The Flathead Beacon is a weekly print newspaper and daily online news source serving Western Montana’s greater Flathead Valley. Headquartered in Kalispell, Montana.

www.flatheadbeacon.com

Earlier this month Steve Scher, host of the popular NPR-KUOW radio show ‘Weekday’ joined me in the field to talk bears. Steve was piecing together a story about the bears of Washington and wanted an opportunity to learn about some of the work GBOP and our partners do on the ground. We met at Tradition Lake near Issaquah and within minutes I was able to show him some fresh bear sign! A beautiful example of a tree stump destroyed by a black bear that was searching for grubs. This forest is a great example of the quality habitat that can be found on the outskirts of a sizeable town like Issaquah, and where conflicts between bears and people can occur. These conflicts usually revolve around non-natural food attractants. A bear in a backyard is just like a dog begging at the dinner table – one reward and he’ll be back for more. The trouble is, once a bear is “food-conditioned” by tasting high-calorie foods like garbage, sunflower seeds, and compost, it is a hard habit to break. As we scoured the forest for bear clues I shared some of these thoughts with Steve who enthusiastically recorded them for his show.

I was excited about Steve’s approach as he was really trying to assess the future of grizzly bears and other large carnivores in Washington State. With fewer than 20 grizzly bears in the North Cascades, their future does not look bright without human intervention (an augmentation of bears from another area would be needed). In contrast, in 2008 wolves made a natural return to the Cascades for the first time in 80 years, and given half a chance, their numbers will increase along with their range. Black bears are doing pretty well in the forested ecosystems of Washington – estimates suggest there are around 20,000 in our state.

What’s good for black bears is good for grizzly bears too, and with that in mind GBOP is always thinking about pragmatic ways for humans and bears to coexist. One of the programs we love is the work of Rich Beausoleil and Bruce Richards, both of whom are carnivore biologists with Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. They are on the frontline of working with bears and people to ensure safety and understanding – for both species! They use Karelian bear dogs to help keep black bears (and cougars) from getting into trouble near human property. This incredible approach to wildlife management is quite something to witness so I introduced Steve to Rich and Bruce that same afternoon. He recorded the sound of a bear being released from a culvert trap with the specially trained Karelian bear dogs in hot pursuit. The recording on the radio sounds pretty dramatic to say the least, but it is all in the bear’s best interest. Instead of capturing a bear at the location where it has gotten into trouble and translocating it (only to find it later return) the new approach (made possible by the use of these dogs) is to release the bear actually right there – in the very place it is finding itself in trouble. Once the culvert trap door opens, the bear bolts out, and the crazy commotion of noise and dogs ensures that the bear will not be back for more! “Tough love” as Rich says. But it works. Steve got a real kick out of meeting Cash and Mishka, the two dogs owned by Rich and Bruce. They are among the best wildlife ambassadors out there.

Next stop was an interview with Cathy Macchio, an incredible lady who has taken it upon herself to arm her neighborhood in the Issaquah Highlands with all the information needed to live peacefully in bear habitat. She has worked tirelessly to help bears and people and we are honored to now welcome Cathy to the GBOP team.

On Monday, Steve invited Rich, Scott Fitkin (US Forest Service wildlife biologist) and myself back to the studio for a live show about bears, cougars and wolves. The show became a great overview of Washington’s carnivore heritage. You can hear the podcast here: http://www.kuow.org/program.php?id=20076

Our thanks to Steve Scher and everyone at NPR-KUOW for supporting our work by helping to spread the word!

Chris Morgan

Co-Director, GBOP

This is an article by K.C. Mehaffey published April 14, 2010 in the Wanatchee World

WENATCHEE — Scientists this summer will launch the first large-scale effort to find evidence of grizzly bears in the North Cascades, setting out 75 to 100 hair snags and a few dozen remote cameras.

“We think there’s a few bears wandering around out there, but it’s probably very few,” said Bill Gaines, wildlife biologist for the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest. “Certainly we have indications the bears are just north of the Canadian border, and likely would wander back and forth,” he said.

Some attempts were made to document grizzly bears in the mid-1990s, he said, and scientists have used remote cameras to follow up on reported sightings. “In terms of a broad-scale effort, this will be a first,” he said.

MOSES LAKE, Wash. – Two Grant County men are expected to appear in federal court next week, accused of shooting one of Washington state’s few grizzly bears. The case stretches back to a hunting trip in October 2007, during which investigators say the men shot a full grown male grizzly in Northeastern Washington’s Selkirk Mountains.

Kurtis Cox and Brandon Rodeback are then accused of transporting the dead bear to property near their homes in the Moses Lake area. State and federal wildlife investigators say they were able to find the burial site.

“Officers found a grizzly bear carcass and a grizzly bear hide and head in two separate holes buried on the family farm,” said Deputy Chief Mike Cenci, of Washington Fish & Wildlife Enforcement. Investigators were able to determine from tests that the bear was a valuable research subject.

State and federal wildlife officers say a tip led them to the suspects and a site where they tried to hide the bear. They released this photo of the bear’s hide. “It had an ear tag,” Cenci said. “Biologists had been tracking that animal for 14 years, so we know a lot about its life history.”

Wildlife groups say killing any member of the state’s struggling grizzly bear population is a big setback to hopes the large bears will reestablish a presence in Washington state. “It really increases the chance that this animal is not going to make it, and we cannot afford to lose anymore bears in the Cascades or the Selkirks,” said Paul Bannick, Seattle Director of Conservation Northwest.

Once plentiful in Washington and most of the rest of the Western states, the grizzlies were all but hunted into extinction. Efforts to protect them have helped increase numbers in Montana, Idaho and Wyoming. The return of the bears to those states has already generated heated concerns from some ranching and hunting groups.

Those same concerns are now being voiced as Washington state prepares for what appears to be the grizzly’s imminent return to this state. Shooting a grizzly in any state is a violation of federal endangered species laws and could lead to six months in jail and heavy fines.

Cox and Rodeback are expected to appear before a federal magistrate in Spokane next week. KING 5 was unable to contact either man today. Court documents indicate the two men explained to investigators they didn’t realize the bear was a protected grizzly, not a common black bear for which Rodeback had a hunting permit.

Source: GARY CHITTIM / KING 5 News

[toc class=”toc-right”]

Bear attacks are very rare though many thousands of people live, work and recreate in bear country. Bears are far more likely to enhance your wilderness experience than spoil it.

Visit our Tips for Coexistence page to learn about preventing human conflicts; remember that it is always good to be prepared for an encounter. You should always carry bear spray while recreating in bear country and know how to use it. Watch this excellent video by our partners at Counter Assault.

https://youtu.be/pc0_GqXKETA

Remember, there is no fool-proof way of dealing with a bear encounter: each bear and encounter is different. Knowing how to interpret their behavior and how to act responsibly is part of the pleasure of sharing our environment with wild bears.

Bears may appear tolerant of people and then attack without warning. A bear’s body language can help you determine its mood. A bear may stand on its hind legs or approach to get a better view, but these actions are not necessarily signs of aggression: the bear may not have identified you as a person and may be unable to smell or hear you from a distance. In general, bears show agitation by swaying their heads, huffing, popping their jaws, blowing and snorting, or clacking their teeth. Lowered head and laid-back ears also indicate aggression.

If you see a bear in the distance, respect the bear’s need for space. Try to make a wide detour or leave the area. If you suddenly surprise a bear at close range, STOP. Don’t crowd the bear – leave it a clear escape route and it will probably exit. Assess the situation: is the bear acting in a calm and curious manner, or is it acting in a predatory or defensive manner?

Defensive confrontations are usually the result of a sudden encounter with a bear protecting its space or food cache, and with female bears with young. Defensive confrontations seldom lead to contact. In defensive confrontations, the bear is threatening you because it feels threatened.

If you suddenly surprise a bear, remain calm and do not run.

Predatory attacks by bears are very rare, but do occur. Any bear that continues to approach, follow, disappear and reappear or displays other stalking behaviors is possibly considering you as prey. Bears that attack you in your tent or confront you aggressively in your campsite or cooking area should also be considered a predatory threat.

From Center for Wildlife Information.

If you have seen a grizzly bear

There are several options if you think you have seen a grizzly bear, but quick reporting is critical – please use whichever option is most convenient. If possible, please contact each of the organizations below.

Please be as specific as possible in your message about the location and time of the observation.

If you need to report an incident

Report all observations and field sign to your local Washington State Patrol Office, Idaho State Patrol Office, the nearest Washington ranger station or Idaho ranger station.

In case of an emergency, call 911

Visit the Products page to see our Bear Safety brochure.

REVISE TO TALK ABOUT BOTH BEARS – CURRENT INFORMATION

If you spend time in the North Cascades and other rural areas of Washington, the chances of seeing a black bear are quite high. You are much less likely to see a grizzly bear. Watching bears in their natural environment from a safe, respectable distance can be thrilling – they are far more likely to enhance your wilderness experience than spoil it. Knowing how to interpret their behavior and act responsibly is part of the thrill of sharing forests and mountains with wildlife.

The vast majority of bears want to avoid humans. Encounters with aggressive bears are very rare.

Below are simple steps you can take while living, camping, backpacking, and horseback riding in bear country. You can also watch our

Bear Safety Public Service Announcement: with WWO founder, Chris Morgan.

The active ingredients in bear spray are capsaicin and related capsaicinoids. There is a significant difference between the amount of capsaicin in bear spray sold for protection from bears, and in the pepper spray sold for protection from human aggressors. Be sure to buy bear spray, not pepper spray, buy a canister that has a spray duration of at least 6 seconds, and follow the directions for use. Consider buying a bear spray holster so the spray is always easily accessible, and consider carrying spray in hand while walking through heavy brush or other areas with poor visibility.

Bear spray is a good last line of defense, but it is not a substitute for vigilance and following appropriate bear avoidance safety techniques. Bear spray is intended to create a wide barrier between you and the bear, so the spray can affect the bear’s eyes, nose, throat, and lungs. Spray when a bear is no less than 25 feet away. Point the canister slightly downwards and spray in 2 to 3 second bursts in the direction of the bear with a slight side-to-side motion. This distributes an expanding cloud of spray that the bear must pass through before it gets close to you. Spray additional bursts if the bear continues toward you. Continue spraying until the bear either breaks off its charge or is going to make contact. Bear spray has been shown to reduce the length and severity of serious physical attacks when used properly. Bear spray should not be used as a preventative measure: never spray your backpack, tent or person with bear spray.

Bears emerging from and returning to their dens have 5 to 7 months to gain enough weight to sustain them through their winter denning. Easily obtainable, high-calories meals like food items in garbage cans, bird feeders, pet food and compost often attract bears and bring them in close proximity to humans. Whether it is a bear’s first visit or a repeat visit to someone’s yard, their presence may lead to conflict. Bears that are fed intentionally or unintentionally by people often lose their fear of humans, may become aggressive, and may cause property damage. Once a bear becomes food-conditioned and habituated, wildlife agencies may be forced to kill it. It is important to remember that ‘a Fed Bear is a Dead Bear’.

Manufacturers of bear resistant garbage cans:

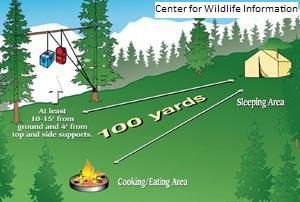

The following tips are equally important whether camping off-trail, or in multi-site campgrounds close to the road: both should be considered part of bear country and should be afforded the same safety precautions. Bear in mind that neighboring campers and campers that have left prior to your arrival may not be taking the same precautions, so be especially vigilant when utilizing campgrounds.

If you spend much time in the rural areas of the western United States, the chances of seeing a black bear are quite reasonable. You are less likely to see a grizzly bear; there are relatively few in the Lower 48 States, found only in northern Washington and Idaho, northwest Montana, and around Yellowstone National Park. Watching bears in their natural environment from a safe, respectable distance can be enjoyable. Positive experiences with wild bears are far more common than negative experiences. Although extremely rare, aggressive encounters between people and bears sometimes occur. Call for any recent reports of bear activity in the area you plan to hike. Bears feel threatened if surprised. If a bear hears you coming, it will usually avoid you. To avoid bears:

The very act of hunting puts hunters at an increased risk of encountering grizzlies; elk bugling, game calls, and cover scents attract not only game, but bears too.

Visit the Products page to see our Bear Safety brochure and the Grizzly Bears of the North Cascades Brochure

Bear signs to watch for: Signs of bear claw marks on trees and logs, ripened berries, paw prints, bear scat (dung) and partially buried carcasses.

[toc class=”toc-right”]

This page presents an assortment of grizzly bear observation accounts that have occurred in or near to Washington State’s North Cascade Ecosystem. We will keep this page updated as new accounts become available.

As stated in the report titled the ‘North Cascades Grizzly Bear Ecosystem Evaluation’ [1], North Cascades grizzly bear observations are rated on a reliability scale from Class 1 to Class 4.

Class 1 (confirmed) reliability rating indicated a grizzly bear observation confirmed by a biologist and/or by photograph, carcass, track, hair, dig, or food cache. Grizzly bear sign required verification by a grizzly bear biologist. Tracks were documented by photograph and/or plaster cast and met grizzly bear front foot toe alignment criteria using the Palmisciano Line Method. If tracks were not of sufficient quality to allow the use of the Palmisciano Line Method, they were rated with a lower reliability. Hair samples were guard hairs identified by microscopic examination of basal and shaft scale patters in combination with shaft shield and shaft tip coloration. If structural characteristics of the hair could not be differentiated, the rating was lowered. Digs and food caches required verification by a grizzly bear biologist.

Class 2 (high reliability) report documented and observation of a grizzly bear that was identified by two or more physical characteristics, but lacked verification criteria as noted for a Class 1 observation. The presence of a shoulder hump, long front claws, and concave facial profile were the physical characteristics used to identify Class 2 observations.

Class 3 (low reliability) rating indicated that the observation report included documentation of only one identifying physical characteristic of a grizzly bear, making it impossible to verify the species of bear observed.

Class 4 (not a grizzly bear) rating was given to an observation that was reported as a grizzly bear, but which, upon investigation, was verified to be a species other than a grizzly bear.

Between 1983 and 1991, there were twenty Class 1 sightings, eighty-two Class 2 sightings, and 102 Class 3 sightings.

From 2003 thru 2008, there were 26 reported sightings. Of these, there were one Class 1 sighting, three Class 2 sightings, and one Class 3 sighting.

Of North Cascades grizzly bear sightings reported to government agencies between 1950 and 1991, 20 were confirmed and an additional 81 were considered highly probable. Today, the estimated resident population in Washington’s North Cascades is fewer than 20 bears — the estimated population in British Columbia’s North Cascades is also fewer than 20 bears. It is likely the home ranges of a few grizzly bears span the international border.

Upper Cascade River watershed, North Cascades, Washington State, October 2010

Photos taken by hiker Joe Sebille in October 2010 appeared to be that of a grizzly bear in Washington’s North Cascades. These were initially thought to be the first confirmed grizzly bear photos taken in the North Cascades in possibly a half-century. However, in 2015, additional photos surfaced taken by others in the same region and during the same general time period of the Sebille photos. These photos were less distant with better lighting and detail and appear to be this same bear — a large black bear with the prominent shoulder hump and other features which made it resemble a grizzly bear, especially in the distant profile as can be seen in the photo below. Read the full press release and see the photos.

Manning Provincial Park, British Columbia, 2010

Just 15 miles north of the border between Washington and Canada this photo (below) of a North Cascades Grizzly Bear was captured in Manning Provincial Park. This is just a mere 2 to 3 hour walk for the bear from Washington State, making it the closest confirmed sighting of a North Cascades Grizzly Bear in years.

Chesaw Grizzly Bear, May 2003

In May, 2003 a rancher witnessed a grizzly bear making its way across his property near Chesaw, Washington. Although this grizzly bear observation was outside the North Cascades Ecosystem, it was only 25 miles east of the North Cascades Grizzly Bear Recovery Zone.

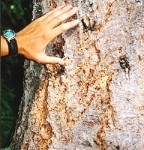

Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife biologists documented by photo, measurement, and plaster cast, several bear tracks found in mud near a spring on the property. They also collected hair samples from a barbed wire fence through which the bear had reportedly passed, as well as bear scat (droppings) found near the tracks and hair. The biologists also found and photographed a small dig site (see below) where a large animal had excavated a ground squirrel burrow, a common foraging behavior for grizzlies, but not typical for black bears

British Columbia Grizzly Bear, 2002

In June 2002, two Canadian hunters came across a grizzly bear in the southern portion of British Columbia. The bear was grazing in a meadow east of Manning Provincial Park (which is directly adjacent to Washington’s North Cascades National Park Service Complex).

Glacier Peak, 1996

In 1996, a bear biologist saw a grizzly bear on the south side of Glacier Peak in the Glacier Peak Wilderness Area.

Thunder Creek, 1991

A photograph of a grizzly bear front track was taken in the Thunder Creek drainage (North Cascades National Park Service Complex) in 1991. This represents a Class 1 level observation, which means that it has been verified as evidence of a North Cascades grizzly bear. To learn more about identifying the difference between grizzly and black bear tracks, click here

Bacon Creek, Whatcom County, 1989

The grizzly bear track photograph below was taken on Bacon Peak (Whatcom County) in 1989. It shows the elongated claw marks on the front track (the lower of the two), and also the “shallow” toe arc that is typical of grizzly bears (and not black bears). To learn more about identifying the difference between grizzly and black bear tracks, click here.

[1] Almack et al. 1993

Thousands of people go camping, fishing and recreating in bear country every year which means there is a need for bear resistant products that you can store your food/catch in.

There are bear resistant food containers, bags so you can hang your food and now there is a bear resistant cooler officially approved by the Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee. It is called the YETI.

YETI Tundra ice chests have been thoroughly tested by the Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee (IGBC) in both controlled simulations and with wild grizzly bears. The IGBC officially approved the YETI Tundra coolers for use on public lands occupied by grizzlies. The IGBC publishes minimum design and structural standards, inspection and testing methodology for BEAR RESISTANT CONTAINERS. YETI Tundra coolers met the IGBC requirement both in the engineered test and the live bear test.

The containers come in many different sizes and price ranges to meet the needs of almost anyone.

It is nice to see this new bear resistant product. Use of the YETI will help keep many bears from getting into human food which in turn will keep them from becoming problem bears.

Submitted by Wendy Gardner

Since his “birth” on August 9, 1944, Smokey Bear has been a recognized symbol of conservation and protection of America’s forests. This is a vintage Smokey Bear shoulder patch, photo courtesy of Dennis Ryan.

His message about wildfire prevention has helped to reduce the number of acres burned annually by wildfires, from about 22 million (1944) to an average of 7 million today. Many Americans believe that lightning starts most wildfires. In fact, on average, 9 out of 10 wildfires nationwide are caused by people.

The principle causes are campfires left unattended, trash burning on windy days, arson, careless discarding of smoking materials or BBQ coals, and operating equipment without spark arrestors.

Smokey Bear is the center of the longest-running public service advertising (PSA) campaign in U.S. history. Since 1944, he has been communicating his well-known message, “Only You Can Prevent Forest Fires.”

This is the debut 1944 Smokey poster.

In 2001, the term ‘Wildfires’ was introduced to include all unwanted, unplanned fires in natural areas such as grass fires or brush fires. The Smokey Bear campaign is a critical tool specially designed to ask for every citizen’s conscientious commitment to be responsible with fire.

A new ad campaign encourages young adults to “Get Your Smokey On” – that is, to become like Smokey and speak up when others are acting carelessly.

Primary source: USFS News, Gary C. Chancey, Wayne National Forest