[toc class=”toc-right”]

Dramatic Declines

Following section extracted from ‘Grizzly bears’, by David J. Mattson, R. Gerald Wright, Katherine C. Kendall, Clifford J. Martinka, National Biological Service.

Grizzly bears once roamed over most of the western United States, from the high plains to the Pacific coast. As settlers moved west across the Great Plains, their contact with these bears increased.

Grizzly bears once roamed over most of the western United States, from the high plains to the Pacific coast. As settlers moved west across the Great Plains, their contact with these bears increased.

Grizzly bears are potential competitors for most foods valued by humans, including domesticated livestock and agricultural crops, and under certain conditions can also represent a threat to human safety. For these and other reasons, grizzly bears in the United States were vigorously sought out and killed by European settlers in the 1800’s and early 1900’s.

Between 1850 and 1920 grizzly bears were eliminated from 95% of their original range, with extirpation occurring earliest on the Great Plains and later in remote mountainous areas (Fig. 1a).

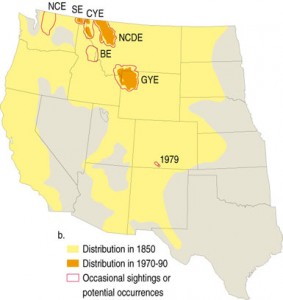

Unregulated killing of bears continued in most places through the 1950’s and resulted in a further 52% decline in their range between 1920 and 1970 (Fig. 1b). Grizzly bears survived this last period of slaughter only in remote wilderness areas larger than 26,000 km2 (10,000 mi2).

Altogether, grizzly bears were eliminated from 98% of their original range in the contiguous United States during a 100-year period.

Protecting Grizzlies from Extinction

Because of the dramatic decline in their numbers and the uncertain status of grizzly bears in areas where they had survived, their populations in the contiguous United States were listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act in 1975. High levels of grizzly bear mortality in the Yellowstone area during the early 1970’s were also a major impetus for this listing.

Grizzly bears persist as identifiable populations in five areas (Fig. 1b): the Northern Continental Divide, Greater Yellowstone, Cabinet-Yaak, Selkirk, and North Cascade ecosystems. All these populations except Yellowstone’s have some connection with grizzlies in southern Canada, although the current status and future prospects of Canadian bears are subject to debate. The U.S. portions of these five populations exist in designated recovery areas, where they receive full protection of the Endangered Species Act.

Grizzly bears potentially occur in two other areas: the San Juan Mountains of southern Colorado and the Bitterroot ecosystem of Idaho and Montana. There are no plans for augmenting or recovering grizzlies in the San Juan Mountains, but serious consideration has been given to reintroducing grizzlies into the Bitterroots as an “experimental nonessential” population.

Grizzly Bears in the North Cascades of Washington

Hudson Bay Company trapping records show that 3,788 grizzly bear hides were shipped from trading posts in the North Cascades area between 1827 and 1859. The decimation of the North Cascades grizzly bear population continued for more than a century with commercial trapping, habitat loss, and unregulated hunting the leading causes of death. The last grizzly bear to be killed in the North Cascades of Washington was in 1967 in Fisher Creek (in what is now North Cascades National Park).

Of North Cascades grizzly bear sightings reported to government agencies between 1950 and 1991, 20 were confirmed and an additional 81 were considered highly probable. Today, the estimated resident population in Washington’s North Cascades is between 5 and 20 bears (the estimated population in British Columbia’s North Cascades is also 5 to 20 bears). Most likely the home ranges of a small number of grizzly bears span the border.

Grizzly bear recovery efforts are now focused on the North Cascades Grizzly Bear Recovery Area.

Grizzly Bears in the Selkirk Mountain Ecosystem

The Selkirk Mountain Ecosystem includes approximately 2,200 square miles of northeastern Washington, northern Idaho, and southern British Columbia, Canada. There are currently believed to be at between 50 – 70 grizzly bears in the Selkirk Recovery Area with numbers approximately equally divided between the Canadian and U.S. portions of the ecosystem.

You can learn about the history of grizzly bears in the Selkirk Mountain Ecosystem as well as the results of a public opinion survey about bears in the area on our Selkirk Recovery Area page.

Chronology of Events

[slider title=”Click to see the chronology of events”]

| Pre-1850s | Grizzly bears are present in all western United States south to the plateau area of Mexico. The grizzly bear population in the lower 48 states is estimated to be between 50,000 and 100,000 individuals. |

| 1827—1859 | 3,788 grizzly bear hides are shipped from three forts in or near Washington’s North Cascades (3,477 from Fort Colville, 236 from Fort Nez Perce near Walla Walla, and 75 from Thompson’s River in British Columbia), according to records of the Hudson’s Bay Company. |

| 1975 | The grizzly bear is listed as a “threatened” species in the lower 48 states under the federal Endangered Species Act. |

| 1981 | In Washington state, the grizzly bear is listed as an “endangered” species under state law. |

| 1983 – 1991 | 153 reports of grizzly bear sightings in the North Cascades. Of these, 21 are confirmed and considered verified Class 1 grizzly bear sightings. |

| 1983 | The Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee (IGBC) is established with the goal of recovering grizzly bears in the lower 48 states. |

| 1986 – 1991 | The North Cascades Grizzly Bear Ecosystem Evaluation concludes that the North Cascades Ecosystem contains sufficient quality habitat (i.e. food, space, isolation, etc.) to maintain and recover a viable grizzly bear population. |

| 1991 | The North Cascades Ecosystem (NCE) is designated a grizzly bear recovery zone by the IGBC. The IGBC identified the zone based on a habitat survey. IGBC recommends that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service begin actions to recover grizzly bears in the area. The North Cascades Grizzly Bear Subcommittee is formed about a month later. The NCE recovery zone is nearly 10,000 square miles – 90% of which is public land. |

| 1992 | The recovery zone boundaries are developed and recommended by an interagency group working on the North Cascades Grizzly Bear Recovery Chapter. |

| 1992 and 1993 | The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service holds public informational and scoping meetings in Seattle, Mount Vernon, Wenatchee, and Winthrop, WA to identify concerns and familiarize the public with grizzly bear ecology and the recovery process. |

| 1995 | Public informational meetings are held to gather comments on the draft North Cascades Grizzly Bear Recovery Chapter. |

| 1996 | A survey of 430 Washington residents is conducted by Responsive Management for the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife to determine the public’s knowledge and attitudes about grizzly bear biology and recovery in the North Cascades. Statewide, 77% of respondents indicate support for recovering grizzly bears in the North Cascades. Respondents living within the recovery zone also largely supported recovery efforts (73% in the western NCE and 64% in the eastern NCE). |

| 1997 | The Grizzly Bear Recovery Plan Chapter for the North Cascades Ecosystem is signed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The North Cascades Grizzly Bear Committee continues to meet twice a year. |

| 2002 | The North Cascades Grizzly Bear Outreach Project (GBOP) begins in Okanogan County (north-eastern NCE). |

| 2003 | The North Cascades Grizzly Bear Outreach Project (GBOP) begins in Skagit and Whatcom Counties (north-western NCE). |

| 2003 | GBOP conducts attitude and knowledge survey of rural Whatcom and Skagit County residents who live in or near to the recovery ecosystem. The telephone survey contractor reports that 76% of 508 respondents are supportive of recovery (52% strongly supportive). |

[/slider]

A Selection of Historical Accounts

Excerpts from Lewis and Clark Among the Grizzlies by Paul Schullery

P 143 and 144

“As Seton and later writers reported, historical evidence of grizzly bears is indeed sparse to nonexistent in the lower Columbia Basin area, though somewhat better the farther you get from the river….In my documentary study of the early historical record (1833 – 1897) of wildlife in the Mt. Rainer area, I was struck by the extreme scarcity of 19th century observations of grizzly bears in that part of the Cascades…Without question, the historical presence of grizzly bears in the Cascade Range north of Mt Rainer has been satisfactorily confirmed… In his study of the early historical record in the area around North Cascades National Park researcher Paul Sullivan quoted early reports from actual sightings…. The most hides traded in any one year at Thompson’s River, BC was 11 in 1851. Apparently 4 hides turned up at Fort Nisqually near present Tacoma … over a period of years…. Sullivan found that much higher numbers of hides came in to the post at Fort Colville, in eastern WA…. The peak year in the GB hide trade there was 1849 when 383 hides came through…. Fort Nez Pierce, near present Walla Walla had its peak year in the GB hide trade in 1846 when 32 hides came through…”

[slider title=”Click to read more historical accounts”]

Following excerpts from Range of Glaciers

by Fred Beckey (2003)

“On June 19 (1859)….the men made camp below the lake’s outlet under a group of firs. That evening, the hunter-guide killed a small grizzly bear amid ‘steep and almost perpendicular cliffs opposite’ the camp. The bear tumbled over brush and rock, Custer reported: ‘The Indians brought it to camp in Triumph, 4 men carried it on 2 poles. This was of course the signal of another enormous feast…. it continued vigorously through the whole night, until the last vestige of the carcass had disappeared.’ Custer found the bear’s meat coarse and not very palatable, ‘except the tongue, which is really an excellent morsel.'” P181 and 182.Custer’s Nooksack.

“Herders generally lost a horse per year and always lost sheep or their way to the high country. The animals either wandered off or were killed by bears or coyotes, and most herders killed every bear they saw, including grizzlies.” P 405. In a paragraph referring to sheep bands in the Lake Chelan, Entiat, Teanaway and Napeequa River areas 1895-1950.

Following excerpts from Valley of the Spirits: The Upper Skagit Indians of Western Washington

by June McCormick Collins (1974)

P 52

“The Upper Skagit hunted deer, elk, mountain goat, black bear (may be brown or cinnamon), grizzly bear, beaver, snowshoe rabbit, fisher, raccoon, and land otter.”

P 147 and 148

Bear was a spirit which gave hunting power. One informant’s father had had this spirit. In dancing during the winter ceremonial, he would dance right into the fire and not be injured because of this spirit…. There is some implication that men who have this spirit tend to have large feet and deep voices as bear-like characteristics….I have already mentioned in passing the special attention given to the bear by the Upper Skagit. In a myth the bear and the ant have a contest to see how long the alternating periods of daylight and night would be.”… (entertaining)… ” The ant won the contest despite his smaller size. The bear then went into a cave for three months each winter….This same myth is also told with rabbit in the character of the ant and with grizzly bear or beaver in the character of bear.”

[/slider]

Learn more about observations.

Learn more about biology and behavior